Sitemaps help search engines and users understand how your website is structured. But not all sitemap types serve the same purpose.

In this article, we break down real sitemap examples across three common types—XML, HTML, and visual sitemaps—so you can see what each one looks like, when to use it, and how it supports a specific purpose.

You’ll also learn basic sitemap best practices to keep your site easy to discover.

What Is a Sitemap?

A sitemap is a file that lists the important pages on your website to help search systems discover and understand the pages you want to make available for indexing—and some of them help users navigate your site.

Sitemaps come in two main formats:

- Extensible markup language (XML) sitemap: A file created for search systems (not humans) that lists URLs you want to be eligible to show in search results

- Hypertext markup language (HTML) sitemap: A regular webpage with links to key pages that helps visitors navigate your site

Here’s a comparison of how XML sitemaps look vs. HTML sitemaps:

Some brands also create visual sitemaps during website planning or redesign. These sitemaps aren’t published for search engines or users—they’re used internally to map site structure, page hierarchy, navigation paths, and other content relationships.

Why Are Sitemaps Important?

Sitemaps help search systems discover the pages you want to show in search results.

Search engines must find each page before indexing (storing) and ranking (showing as a listing) it in search results. Here’s a high-level look at how this process works for traditional search engines:

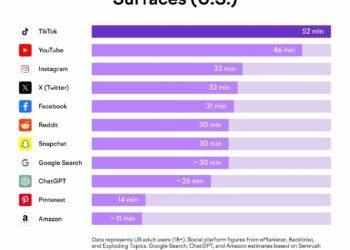

Your content is also more likely to appear in AI-generated responses when important pages are listed in a sitemap. AI tools have their own crawlers and can also use results from search engines.

Effectively, having an up-to-date sitemap helps you avoid the following problems:

- Pages that have no links pointing to them

- Inefficient crawling due to a large site

- Complex or inconsistent structure that confuses crawlers

XML Sitemap Examples

An XML sitemap is a file that helps search systems discover and crawl your website’s pages.

You’ll typically find an XML sitemap at a URL like “yourwebsite.com/sitemap.xml.”

Below are real examples of XML sitemaps that list all key pages for efficient crawling:

Samsung XML Sitemap

Samsung uses a sitemap index file to link to many region-specific sitemaps, which helps manage their global site.

This Samsung sitemap is a good example of how large enterprises handle international SEO.

Best Buy XML Sitemap

Best Buy uses a sitemap index made up of multiple compressed .gz sitemap files, reflecting the scale and complexity of its product catalog.

Each .gz file is a compressed XML sitemap that contains its own set of URLs. Because the files are compressed, it reduces the overall size of the sitemap and allows for more efficient crawling.

OpenAI XML Sitemap

OpenAI uses a relatively small XML sitemap that lists high-priority pages.

This minimal approach shows that effective XML sitemaps prioritize crawl efficiency over exhaustive URL coverage.

HTML Sitemap Examples

An HTML sitemap is a webpage that organizes links to important sections of a site to help users find what they want.

Here are some real examples of HTML sitemaps:

Microsoft HTML Sitemap

Microsoft’s HTML sitemap organizes links to broad, top-level categories with clear subcategories, making it easier to navigate their large, content-heavy site.

This structure works well for enterprise websites with a lot of products, support resources, and informational pages spread across multiple sections.

Walmart HTML Sitemap

Walmart’s store directory functions like an HTML sitemap by organizing store locations and major site sections into a single, browsable page.

This structure helps users explore departments and regional pages without relying on the primary navigation, which is useful for large retail sites with extensive location-based content.

Apple HTML Sitemap

Apple’s HTML sitemap groups links by product lines and support content, allowing visitors to browse all major sections of the site from a single page.

This clean, product-focused structure supports quick scanning and straightforward navigation.

Visual Sitemap Example

Visual sitemaps are planning documents used before website development to map site structure and navigation.

Most visual sitemaps show page hierarchy, navigation flow, and content relationships using boxes, lines, and flowchart-style layouts. These inclusions make it easier to determine how pages should interlink.

This simple visual sitemap example shows how top-level pages branch into related sections, helping teams validate hierarchy and navigation paths before content is created.

Designers often create visual sitemap examples in tools like Figma, Sketch, Adobe XD, or Writemaps. These tools let teams collaborate and align on site structure before development starts.

Understanding XML Sitemap Structure

These tags are used in XML sitemaps to communicate information about the pages listed:

- <sitemapindex> is the root tag used in a sitemap index file. It groups and references multiple sitemap files, which is common for large websites with many URLs.

- <sitemap> defines a single sitemap entry within a sitemap index

- <urlset> is the opening tag that wraps all URLs in your sitemap. It defines the protocol standard your sitemap follows.

- <url> contains information about a single page. Each page included gets its own <url> entry with nested tags inside.

- <loc> specifies the exact location of the resource being referenced. In standard XML sitemaps, this is the URL of a webpage. In sitemap index files, <loc> can also point to the URL of another sitemap file.

- <lastmod> shows when the page was last modified using YYYY-MM-DD format. Search engines may use this value to inform recrawling decisions, but only when it’s kept accurate and updated consistently.

- <changefreq> suggests how often the page content changes (daily, weekly, monthly, etc.). While Google ignores this tag, other crawlers may reference it.

- <priority> indicates the relative importance of pages on your site using values from 0.0 to 1.0. Google ignores this tag, but it can help you identify the pages that matter most when reviewing or maintaining your sitemap.

Many content management system (CMS) platforms like WordPress generate XML sitemaps automatically. You can also easily create one using a sitemap generator tool.

After creating your XML sitemap, you can submit it directly to Google to help it discover and process your important pages.

XML Sitemap Best Practices

Include Page Priority If Desired

Use the <priority> tag in your XML sitemap if you want to indicate which pages you consider more important relative to others, using values from 0.0 (lowest priority) to 1.0 (highest priority).

Google ignores the <priority> tag, so it’s unlikely to have an impact on crawling.

Indicate Change Frequency If Desired

Use the <changefreq> tag if you want to indicate how often a page’s content is likely to change.

Valid <changefreq> values include:

- Never: Archived content that won’t change again, like historical records

- Yearly: Content updated annually, such as event calendars or annual reports

- Monthly: Pages with monthly updates, like feature pages or recurring columns

- Weekly: Content updated weekly, including blog sections or product listings

- Daily: Frequently changing content, like news sections or daily specials

- Hourly: Rapidly changing information, like weather or traffic data

- Always: Real-time content that changes constantly, such as stock tickers or live data feeds

Google ignores the <changefreq> tag, so it’s unlikely to make a difference.

Avoid Duplicate Content

Only include unique, canonical pages in your sitemap to ensure search engines don’t waste time and resources (known as “crawl budget”) on unimportant content.

A canonical URL is the preferred version of a page that search engines should treat as the primary source when multiple URLs show the same or very similar content. You typically specify this using the rel=”canonical” element.

Let’s say that both “yoursite.com/product” and “yoursite.com/product?ref=email” show the same content. In this case, you would only include the canonical version (which is “yoursite.com/product”) in your sitemap.

Common sources of duplicate URLs include:

- URL parameters that create multiple versions of the same page

- HTTP and HTTPS versions of the same URLs

- WWW and non-WWW versions of the same URLs

- Printer-friendly page versions of your URLs

Avoid Noindex Pages

Pages with a noindex directive tell search engines and AI tools to keep them out of search results, so don’t include noindex pages in your sitemap.

Excluding noindex URLs keeps your sitemap focused on content you want visitors to find through search.

Use Multiple Sitemaps

A single XML sitemap can include no more than 50,000 URLs and must be smaller than 50 MB, so use multiple sitemaps organized with a sitemap index file if your site exceeds those limits.

Large websites often split sitemaps by content type—such as blog posts, product pages, etc.—to make it easier for search engines to crawl and understand the site structure.

Ensure Your Sitemap Is Error-Free

An error-free sitemap helps search engines and AI systems crawl your webpages properly.

Use Semrush’s free SEO checker, Site Audit, to find and fix common sitemap issues alongside other technical SEO issues.

Enter your website and click “Start Audit.” SiteAudit automatically detects and checks your sitemap.xml file as part of the audit.

After the crawl finishes, open the “Issues” tab and search for “sitemap” to surface problems tied directly to your sitemap.

Click “Why and how to fix it” on any issue to see guidance for resolving the problem. Click the linked part of the text to see the specific URLs that are affected.

Resolving these issues keeps your sitemap aligned with your site’s structure and supports stronger technical SEO.

Try Site Audit today.